HISTORY: The Great Migration to Oregon – and those who made it

Published 8:33 pm Friday, June 13, 2025

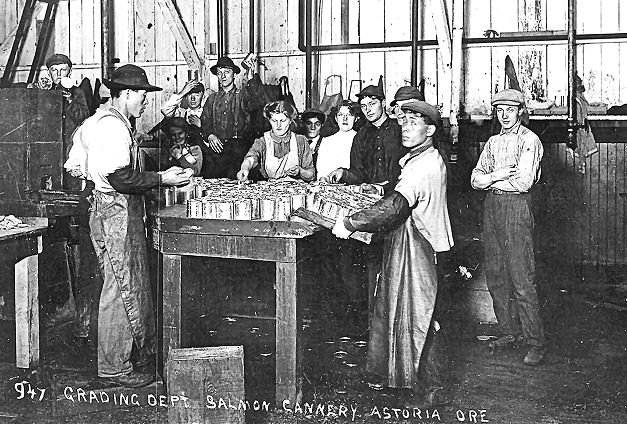

- More than 4,000 Chinese men worked at various salmon canneries in 1881 near Astoria. This photo is of Chinese workers, and some of Scandinavian heritage, working side by side, in the grading department of a salmon cannery. (Courtesy of Clatsop County Historical Society)

We’ve regularly written in this space about the origins and growth of Inner Southeast Portland from its earliest days, and occasionally about the period before that. But what about the melting pot of nations who gave us our communities today? That’s our topic this month.

At the base of the Statue of Liberty on Ellis Island in New York Harbor is an inscription. The most famous of these lines say, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”.

On October 28th, 1886, President Grover Cleveland accepted the Statue of Liberty from France, our greatest ally in the successful War of Independence from Great Britain. But it wasn’t until 1903 that that inscription – part of a poem called “The New Colossus”, written by American poet and essayist Emma Lazarus – appeared on the base of that monumental gift from France.

By that time, many immigrants from around the world had already passed our gates and settled in our country. These words were a strong and emotional statement for immigrants already living in America, and for anyone thinking of coming to America, as well as for Americans born in this country. But it was a promise not always entirely kept – where you came from entered into it.

Many of these immigrants migrated to the Northwest – to work on our railroads and our streetcar system, to labor in our canneries, to harvest our trees, and to farm our land. They were responding to a shortage of workers – and helping to support a rising economy in Oregon. Let me touch on just a few of the nationalities coming to the Northwest – why they came here, and what they accomplished. . .

Cantonese Chinese began appearing in Oregon as early as the 1850s. Small groups of Chinese miners arrived in Northern California seeking to work in the gold mines, and eventually making their way north to reported gold strikes in Southwestern Oregon. They continued their journey, following the trail of gold claims into portions of Washington and Idaho. And when the gold veins began to peter out, work became available to them constructing the Transcontinental Railroad.

By the 1860s, Chinese were traveling to the shores of the Northwest to flee a homeland rife with warfare and famine. Arriving on steamers and sailing ships, Chinese natives disembarked at the major ports in San Francisco, Portland, Tacoma, and Seattle, looking to learn a trade and start a profession – but many were faced with having to settle for whatever menial jobs they could find.

On April 16th, 1868, the newspapers in Portland and Oregon City reported that thousands of people gathered on the east side of the Willamette River for the driving of our own local golden spike, to signal the start of construction of Portland’s first railroad southward to the gold mines in California. We’ve told its stop-and-go construction story in a past article, but there was much excitement at its start, anyway.

As spectators cheered and applauded the procession of railroad officials and dignitaries who appeared and made speeches that day, few noticed the contingent of Chinses laborers who were standing with picks, axes, and shovels – but they were the ones who would be performing the painstaking and backbreaking work of laying the tracks southward for the planned Oregon and California Railroad.

Many Chinese, however, remained in the city, living along Portland’s waterfront, and hiring on as dishwashers, cooks, laundrymen, or unskilled laborers. Many laundries run by Chinese merchants could be found in East Portland along Union and Grand Avenues, where foreign-born people could afford the rent for space in which to start up their new businesses.

Interestingly, Carl Abbott in his book “Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People” reported that by the late 1880s the Chinese were operating more than 100 shops and stores. Quite an accomplishment, in a prejudiced time when many people deemed the Chinese immigrant as fit only for menial work.

Chinese workers were also drawn to farms, lumber camps, and the salmon packing plants that had been springing up near the Columbia River in the 1880s. More than fifty canneries lined the Lower Columbia River, and over 4,000 Chinese cannery workers lived in shanties near the now-long-gone town of Knappton, Washington, just a few miles east of the Astoria-Megler Bridge.

Closer to home, local historian and long-time Westmoreland resident Eileen Fitzsimons has come across information in the Old Sellwood City Records that Chinese lived there as early as 1887. Though not identified by name, the records show a Chinese man operated a “laundry near the creek in Sellwood”. Also, a 1900 census indicated a Mr. Boe was employed as a gardener, and a Mr. Ling as a fisherman, and both resided either on Ross Island or near the Midway subdivision at the north end of today’s Westmoreland.

As mentioned, however, that era harbored prejudices – and we cannot say were are without any even today. In 1907, reports of harassment against a man employed as a domestic at the Golf Links near Sellwood were published in the newspapers. And as Mrs. Fitzsimons has pointed out in her articles in THE BEE, racial exclusionary language was written into many deeds by the real estate companies at that time, to block immigrants from owning a home in many sections of Westmoreland.

The largest contingent of Chinese workers in Inner Southeast was south of the town of Sellwood, at the “Llewellyn Orchards”. Seth Luelling (who had changed the spelling of the family name to Llewellyn) converted his newly-acquired 100 acres from Joseph Meek into a new orchard, and employed 20 to 30 Chinese to cultivate and look after the plants and trees there. To keep the Chinese nurserymen in line, and to communicate with them in their own language, Ah Bing – a stocky Manchurian Chinese who stood close to six feet tall, as were most natives raised in the Northern Section of China – was hired as foreman to oversee these workers. (We have previously told how Mr. Bing developed a very popular new cherry variety in that orchard – which still carries his name today.)

While there’s isn’t any physical or written evidence of where these immigrant workers lived, it was most likely that their shacks were built close to the Llewellyn Orchards where they worked – along portions of today’s Waverley Country Club, and in or near the Garthwick community at the south end of Sellwood.

Because of the public outcry by American workers who feared cheap labor was threatening their jobs, the U.S. Government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Stringent limitations were imposed on the Chinese people in it, blocking any additional Chinese from immigrating into America. Regrettably, there are echoes of this type of attitude in our society even today.

Young Japanese men, looking to better themselves, arrived in response to the targeted exclusion act, seeking to fill the void left by the vacant jobs once occupied by the Chinese. Most of these men supported themselves as seasonal laborers, traveling to farms – or by hiring on as domestic workers in low-paying jobs for wealthy families. Other Japanese workers could be found around the Northwest side of Portland’s Waterfront District, working as cooks or dishwashers at restaurants.

Later, Both Japanese and Irish immigrants were needed to augment Chinese railroad crews when America was ramping up the building of the Transcontinental Railroad connecting the Eastern United States to the West Coast, to be finished with its own Golden Spike ceremony upon completion.

It wasn’t long before Japanese men turned to farming on the outskirts of Portland, and they were soon prevalent throughout the Hood River District. In Portland, small stores and boarding houses operated and owned by Japanese could be found along the northern waterfront.

As early as the 1860s and onward, Portland was growing at a rapid pace. With Oregon’s abundant forests, and the Willamette Valley’s bountiful farmland for growing hops and wheat as well as many other crops, there were plenty of jobs available for those willing to work and not enough people available to do the task. Desperate for additional workers, Portland businessmen and investors looked overseas to fill the shortage.

That meant another influx of immigrants. In the 1880s and 1890s, it was an influx of Scandinavians – many of them skilled as loggers, fishermen, and farmers – who were drawn to the Pacific Northwest: Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, and Finns, who had already migrated to the Midwest from their home countries twenty years before, now resumed their westward migration, encouraged by relatives who had already settled in Portland, Tacoma, and Astoria.

It was a difficult journey, particularly for Scandinavians who had few funds to support such a trip. However, with the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10th, 1869, it became much easier and cheaper for immigrants to travel from the Midwest to the Pacific Coast. Scandinavians could take the train to San Francisco, and then travel northward by coach – or pay for passage aboard a steamer – to reach Portland.

The first wave of Scandinavian immigrants were Norwegian, who had emigrated to America for religious reasons. Tales of Oregon’s lush forests and fertile land, reported as being similar to those in their homeland, attracted many Nordic families – but, when they disembarked at Portland’s waterfront, it was financially expedient to accept work in whatever positions were available in the big city. Many found temporary housing in cheap hotels or boarding houses in the Albina district. Other families could be found in the Irving and Overlook district of Portland.

Eventually many Norwegians moved on to Astoria to work in the lumber camps, in shingle mills, and to fish along the Columbia River or labor in the salmon packing plants. They were instrumental in helping transform the economy of Astoria, the population of which, in that era, almost surpassed Portland’s!

When the Schindler Furniture Factory bought acreage in the town of Willsburg, just east of Sellwood, they relied on the skilled craftsmanship that Scandinavians exhibited – experienced in the craft as tradesmen, journeymen, and artisans. Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes – along with a contingent of skilled German craftsmen – were hired on to run the mill’s machinery and to construct the bed frames, chairs, dinette sets, and dressers sought by upscale residents on the west side of the Willamette River.

Meantime, many Finnish and Swedish immigrants were attracted to sections of the Columbia River, because of the salmon and smelt there. Because many of these Scandinavians were proficient as fisherman and sailors in their own homeland, they were able to easily integrate into the Northwest along the rivers, and along the coast as well. Many Finnish and Swedish seafarers settled in the communities of Clatskanie and Astoria, as well as at Chinook and Ilwaco in the State of Washington.

For Finnish workers not attracted to rough work on the river, there was land available near the Columbia River for operating dairy farms and peppermint fields. Many of them established farms and raised cattle near Warren and Scappoose. And, for the lumberjacks among them, the native Douglas firs in the surrounding hills provided a source of income.

Of all those immigrants who resettled in America from Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, and Finland, the Swedish people contributed the largest number of Scandinavians. Fleeing crop failure, land shortages, rising taxes, and famine, Swedes immigrated to this country in search of social, political, and economic opportunities. And, seeking relief from religious persecution, there were the Swedish Baptists, Methodists, and more.

As for the Danish – they came to Portland, lured by news that land in America was plentiful, and that the government was practically giving it away. Farming was a major occupation in Scandinavia at that time, but few could afford to own the land or make a profit renting and working the farmland in their own country; many immigrants took advantage of the United States’ Homestead Act of 1862, which granted 160 acres of land to any adult – provided they worked and improved the land for at least five years.

Oregon welcomed the Homestead Act, because it was intent on opening its fertile lands to these newcomers. Native-speaking Scandinavian agents were hired to convince Swedish families living in the Midwest to journey to, and settle in, the Pacific Northwest. Enticing photos and persuasive pamphlets were distributed in communities in the Midwest picturing the Oregon Country as a land ideal for farming, with sparkling-clean water and newly-built homes plentiful for starting a family. Neighborhoods were already established here with Swedish speaking people, Swedish schools, and Swedish Lutheran Churches, they were told – all waiting with open arms to welcome their fellow countrymen.

“Passage aboard trains was offered for incredibly low prices, and land was available for mere pennies,” Victoria Owenuis elaborated in her essay on the early Swedish Americans in the “Oregon Encyclopedia”. Many Swedish families arriving in Portland for the first time made their new homes in the Albina and Irvington neighborhoods. Since there wasn’t much farmland to purchase inside the metropolitan Portland area, Swedish workers choosing to stay here had to hire on to lower-paying jobs as manual laborers. Such work as longshoremen on the Portland Docks, working in the various fruit canneries, or in furniture and brick factories, was their only means of support if they chose not to head for the countryside and start a farm.

At that time, the Swedish established a productive community in North Portland, with a Swedish hotel, Swedish grocery stores, Swedish bookstores, and Swedish pharmacies. There were various Swedish religious congregations, and even their own newspaper – “The Oregon Posten”.

Local Swedish contractors and laborers helped build the Ross Island, St. Johns, and Burnside Bridges over the Willamette River. But working the land remained in the hearts of most Swedish immigrants, and once they saved enough money to do so, they moved on once again – to Astoria, Coos Bay, and North Bend.

In her essay, Victoria Owenuis pointed out that east of the Willamette, the first Swedish settlement in Oregon was already operating in Powell Valley. A Swedish agricultural colony, east of Gresham, was composed mostly of dairy farmers, and they had their own school and three different church groups there.

As with other nationalities who migrated here and became hardworking citizens of America – alas, the Swedes were persecuted, too – especially during the First World War. Overzealous Americans, became suspicious of any Europeans living here who didn’t speak English. Those who were flying the Swedish flag, attending Swedish-speaking church services, or following any tradition from their homeland that was different from what Americans did, were shunned by many.

To avoid this treatment, many people of Swedish extraction reluctantly stopped attending Swedish organizations and churches, and arranged that their church sermons be delivered in English only. Despite this deplorable treatment, Swedish families continued to embrace the American way of life.

Suspicion, distrust, and discrimination greeted them all as they came to our country – Chinese, Japanese, Norwegians, Finns, Danes, and Swedes – not to mention immigrants from other countries all around the world – but all were drawn by the American promise, as poorly kept as it may have seemed upon their arrival, and all of them did play a crucial role in improving this nation’s economy, bringing about political reform, and broadening the American “Melting Pot”.

I must point out that the peoples profiled in this article weren’t the only newcomers who helped reshape America. In the next issue of THE BEE, I will go on to explore the arrival of the Germans, Russians, Greeks, Italians, and Poles here in the Great Northwest.

They all played a part in the great pageant of our local, and our nation’s, history!