HISTORY: Revisiting the forgotten town of Willsburg

Published 12:00 am Sunday, December 22, 2024

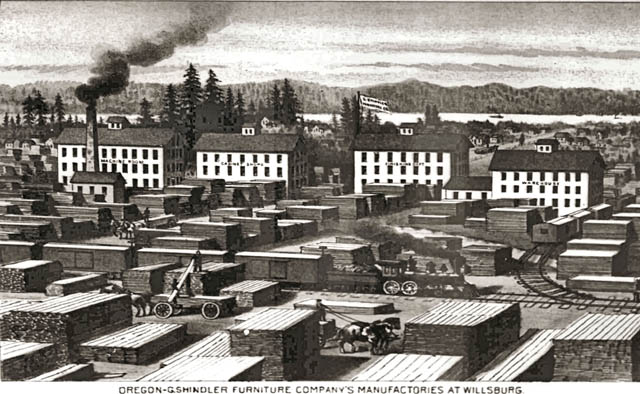

- This fanciful illustration of Willsburg’s Shindler Furniture Factory in its golden days was published in 1888 in the West Shore Magazine. The factory employed up to 75 men, and operated in Willsburg for about 12 years. This illustration exaggerates the buildings, the surroundings, and the placement of the river – but still, you get some idea of what they looked like then!

Portland has changed a great deal in just the last few decades, but in this space we have found many tales to tell of places and people here in the past. However, although neighborhood names reflect past independent communities in many cases, it’s a fact that some past communities – recognized towns, in Southeast Portland – have entirely vanished. This is the story of one of those.

Trending

Long before Reverend John Sellwood acquired the property that would eventually name a community after him, and certainly well before the Sellwood Ferry and the Sellwood Trolley existed, the town of Willsburg was being established just east of present day Sellwood by pioneers George and Jacob Wills.

If Willsburg sounds vaguely familiar to you, that might be because you were reading this newspaper fifteen years ago when I presented a story in THE BEE about one of the area’s first pioneers, and told a bit about the town then. For those that missed the story, or who have moved here recently, I thought it might be time to add additional information I’ve collected about Willsburg, and update everyone on one of Southeast Portland’s forgotten chapters of our history.

Between 1840 and 1860, over 400,000 people drove covered wagons over the arduous route that started primarily from Independence, Missouri, and ended in Oregon City, with many of those travelers of the Oregon Trail settling along different portions of the Willamette Valley after their arrival. They came on the promise of fertile land, abundant game, and the chance to start a new life and escape from the woes they left behind. Among those traveling that trail were George and Sarah Wills and their family.

The Wills family arrived from Oskaloosa, Iowa, via the Oregon Trail in 1847. George and Sarah laid claim to 641 acres of land, which included much of today’s Eastmoreland neighborhood, south past Johnson Creek – and included today’s Tacoma Street, as well as parts of the current city of Milwaukie. A son, Jacob Wills, who married Lorana Bozarth on August 22, 1849, laid claim to an additional 620 acres of his own, just north of his parents’ property.

With the land around them forested with Douglas firs and tall cedars, George and his son Jacob decided that harvesting the trees for lumber would make for a profitable enterprise. Together they erected a ten-foot dam on Johnson Creek, partnering with Edward Long, to erect a water-powered sawmill there.

Life was far from easy for such early Oregon pioneers. For the Wills, it meant cutting down trees by hand and hauling them with teams of oxen to their mill – after which, finished lumber had to be transported by horse and wagon to the town of Milwaukie, where it was loaded onto schooners bound for California or the Hawaiian Islands. With no easy access to the Willamette River close to the Wills’ farmstead, the only other option they had for delivering cut lumber, besides getting it to the Milwaukie harbor, was an overland journey to the Stark Street Ferry in East Portland.

Jacob’s son A.N. Wills recalled that lumber from the Wills Sawmill was later hauled up Spokane Street to the ferry landing by the Willamette River, and loaded aboard clipper ships, well before the town of Sellwood existed.

Although that Ferry landing was only about five miles away, loading a wagon full of heavy timber and traveling through a thick forest of trees with it was easily an all-day journey. Once they arrived at the Ferry Landing, they had to wait their turn for the trip across the Willamette to find a prospective buyer, besides unloading the wagonload of timber. While the Wills’ men were kept busy at the sawmill, younger family members had their own chores – attending to the family garden, washing clothes in Johnson Creek – or, for fun, fishing for salmon up Johnson Creek from the Wills’ dam.

On January 24th, 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, near Sacramento in Northern California, and would-be gold miners flocking there created business opportunities. George and Jacob celebrated their own bonanza, knowing that those gold seekers would lead to much construction in the Golden State. Thousands would-be 49’ers would flock to California to seek their own fortunes, leading to lumber being in high demand for houses, stores, and even for the construction of sluice boxes to be used to extract the gold from the tailings in the creeks there. And Wills’ Lumber Mill would be among those filling the orders!

Edward Long, who was married to George’s daughter Martha Jane Wills, eventually decided that the chopping and hauling of wood was too dangerous an operation for him to continue in as a partner, so he sold his interest in the sawmill to the Wills family, used the money to buy a land claim from Seth Catlin, an earlier pioneer. Edward and Martha then devoted their time to a peaceful life of growing apples on their orchard on the west side of today’s Milwaukie Boulevard between Holgate Boulevard and Reedway Street. The short street of Long, just north of Westmoreland, was named after him. So there we leave Edward Long, and return to tale of the Wills family.

Ever a devoted Baptist, George Wills delighted in sharing scriptures from the Bible with his hired hands during and after working hours. One of his first missions when arriving in Willsburg was to build a church, which when completed was called the “Hard Shell Baptist Church”. The Wills family’s memorandums record that George always dressed up in a red shirt on the Day of Sabbath. Besides offering Sunday services, the Willsburg church also was used as a gathering place for neighbors to celebrate the yearly harvest, to hold some social functions, and to provide space for meetings of various sorts.

In April of 1868, two of Portland’s most wealthy and prominent businessmen, Ben Holladay and Simon G. Elliot, were engaging in a bitter contest to see which of them could first build a railroad south through the Willamette Valley to the California border. Holladay, who represented the eastside railway, negotiated a right of way for his Oregon-California Railway right through the Wills’ property. It seemed to the Wills this was an ideal convenience for shipping their lumber by rail, and it would also provide a railway stop for passengers or workers visiting this section of Southeast Portland. The subsequent railroad construction was slow and often paused for significant intervals, but this plan led eventually to the right of way used by today’s Union Pacific through that same area east of Sellwood.

As timber sales decreased after the peak of California’s gold rush, new communities began forming on the east side of the Willamette River – but few people chose to settle on Wills farmland. While many still spent their days there, drawing wages at the sawmill, the Donation Land Claims owned by George and his son were not a destination for workers’ homes and families. Both George and his son Jacob realized that for that to change, a town must be platted and a community started. So, by 1870, Jacob Wills had laid out a sixteen-block townsite, called Willsburg – the west side of which was approximately along today’s 24th and S.E. Tenino, and continued east past the Oregon and California Railroad Tracks.

Longtime Willsburg resident Mrs. Ortley Plimpton surmised that eight families lived in the town at that time, and fifty farms and houses were scattered in the surrounding area. Mrs. Plimpton also recalled that a man arrived twice a week in a wagon pulled by two horses to deliver fresh meat in the neighborhood. This was considered a luxury by many residents. He rang a hand-held bell to let customers know that he was waiting patiently at their front gate; and he continued to supply the locals until meat markets opened in Sellwood and Milwaukie.

Before Edward Long departed to grow his orchard, he and Jacob Wills and Edward Long had been asked help to build a dam on Johnson Creek to provide power for a small furniture factory. The mystery now is, who did the asking? Seth Wills, in an interview with Fred Lockley of the Oregonian, stated that it was Lewelling and Beard who’d requested the dam be built. Willsburg resident Mrs. Ortley Plimpton, as reported by the Milwaukie Review in 1953, said it was the trio of Powers, Doily, and Bread. Recalling events years later can be a challenge.

But, as Mrs. Plimpton stated, this early furniture factory manufactured simple items such as “spindle beds and chairs, rawhide laced seat chairs”, along with tables, bedsteads, and head boards. The furniture factory operated near S.E. Harney Street, just west of the railroad tracks, and we do know Jacob and Edward helped with the start of that factory.

The town of Willsburg began to show promise, but it still lacked a general store and a meat market, and people had to travel to Milwaukie to pick up their mail. But what most families valued most was having a school for the children, and they had one.

Worried that her children had to walk miles to attend school in Milwaukie, Jacob’s wife Lorana Wills had donated a portion of her land on which a new school was to be built. The first meeting for Willsburg School was held at Jacob Wills’ cabin in 1877, in which community leaders gathered to outline the conditions for, and to decide the appropriate taxes to levy to support, the Willsburg School. Located on one and three quarter acres, up on a hill overlooking Johnson Creek, the schoolhouse was constructed with lumber cut at the Wills Sawmill. The school building was 60 feet long and 30 feet wide, with a ten-foot porch on the front, and a small belfry. A bell rope that hung from the belfry was used by the janitor to call the students to class. Fifteen students attended the classes taught by Miss Amy Kerns.

The Hungren and Shindler Furniture Company was known as one of the Northwest’s oldest and largest manufacturing firms. Gabriel Shindler had been a successful furniture salesman since 1857, when he first opened his showroom in Portland at Salmon and First Street. The company specialized in supplying hotels, boarding houses, private residents, and even steamboats. But “spontaneous combustion” was not yet well understood, and – as had happened at other similar factories across the country that had buildings filled with oily rags, bits and pieces of cut lumber, and open containers of paints and varnishes – a fire broke out in 1857, destroying the manufacturing facilities of the Hungren and Shindler Furniture Company.

Shindler came to Willsburg in a search for a place to build a new factory and he came across the now-defunct Lewelling and Beard chair and furniture company. He negotiated to buy ten acres of land, and brought in new machinery that would soon be powered by water and steam from Johnson Creek. With a year’s supply of ash, maple, spruce, cedar, and walnut on hand, the furniture factory was soon up and running, cranking out great loads of furniture that were shipped to the company’s showroom at First and Front Street.

Shindler hired between 30 and 40 men – mainly skilled craftsmen from Germany, and other Scandinavian countries – who produced chairs, tables, and school and hotel furniture out of the ash and maple wood from the Oregon forest. “600 desks were ordered for the Park High School building” in Portland, it was recorded. The Commercial Hotel in Salem also placed an order to supply their new Oregon hotel with furniture and mattresses. The sixty-room hotel connected to Salem’s Historic Reed Opera House was furnished with dining tables, plush upholstered parlors, bedroom sets, and other high-end items – all from Shindler’s Furniture Factory in Willsburg.

At about this time Shindler accepted a new partner, J.S. Chadbourne, who was a major furniture dealer hailing from San Francisco.

Jacob and George might have been getting concerned about the slow growth of Willsburg, especially when there were stirrings of a new commercial district beginning to form just west of Willsburg along Umatilla Street in what would be called Sellwood. And the Sellwood Real Estate Company was advertising lots for sale in that new town, enticing families to purchase property and build homes.

Few people were interested in starting a family in a community filled with the smells and sounds of a sawmill filtering through the neighborhood. And, with the presence of a furniture factory in Willsburg, it seemed the town was destined to become no more than an industrial district. But Willsburg did gain enough interest from residents by 1883 that a Post Office was finally authorized there, and J.F. Rhodes was announced as its new Postmaster. A train depot was also built along the east side of the train tracks, at around today’s S.E. 27th and Tenino Street, and the depot served the community as a Post Office and a general store, as well as a waiting room and ticket office.

A note of interest: When J.F. Rhodes finished serving as Postmaster for Willsburg, he later became the Principal at Sellwood School, and he later transferred over to the Brooklyn School at S.E. Pershing and Milwaukie Avenue.

Workers from the Shindler Furniture Factory began visiting what some residents in Sellwood called their racy side of town, along 17th Avenue just west of Willsburg. It was there that full-time and temporary workers congregated during the evening hours to enjoy the lively saloons. 17th Avenue also was becoming the location for new grocery stores, meat markets, a feed store, a blacksmith shop, and even a hotel for temporary workers looking for a place to stay a night or two until they found permanent quarters. Those living along 17th Avenue could easily walk to work in Willsburg – which still lacked most of such amenities – and then walk back to their home in the evening.

The dynamics of Willsburg changed when the founder George Wills passed away quietly in 1888. Suddenly the welfare of the town no longer revolved around the success of the lumber mill – which shut down after more than a quarter of a century serving the area. It had been claimed to be the oldest sawmill anywhere in Oregon, set up in the middle of a virgin forest. But new ideas and changes were happening in Willsburg.

Jacob Wills established a brickyard in 1889, and the Wills Brick Factory produced many of the bricks used in the construction of homes built on the west side of the Willamette River. All of the facings on the former Oregonian building, now torn down, came from the Wills Factory – as did the facing on Portland’s first high school, Park High, in downtown Portland. The brick factory was run by Jacob’s sons, Alfred Napoleon Wills and Seth Dallas Wills, and operated for about nine years.

When Reverend George A. Rockwood arrived in Portland, he was looking to establish a new congregation. He looked no further than Willsburg: When the Willsburg Baptist Church lost George Wills, its leader, Rockwood helped organize the Christian Endeavor Society, and formed the Willsburg Congregational Church. The structure was finished in October of 1892, providing an alternative for religious observance.

Spontaneous combustion remaining a bit of a mystery at that time, in 1890 a fire once again broke out in the varnishing rooms of the Shindler Furniture in Willsburg, caused by flammable materials stored in the factory. The fire soon spread to the engine room and the dry house, both of which were completely destroyed. The only fire engine available to respond was six miles away in Portland, and couldn’t arrive in time to save the three buildings. This mishap played a good part in Gabriel retiring from the furniture business. Gabriel and his wife Janette spent their last days in Long Beach, Washington, near the mouth of the Columbia River.

By the turn of the Twentieth Century, the town of Willsburg was moving away from its reputation of being an industrial district. August Wilson herded a few cows together and operated a dairy which would deliver milk, cottage cheese, and other dairy products to Sellwood and beyond. Wilson’s Willsburg Dairy was just one of the many hundreds of small operations scattered across the suburbs. W.H. Brown also operated a Dairy at Willsburg that not only delivered dairy products but also offered chickens and dogs for sale. Leghorns and Buff Rock chickens were the choice in poultry, and fox terriers and were raised on his property for those seeking canine companionship.

With few residents in town to support it, the Willsburg Post Office closed down that year, and the community’s residents had to travel to the Sellwood Post Office on 13th Avenue to mail letters and send out parcels and packages, though carrier service for mail delivery was still available.

Parents were protesting the closure of Willsburg School, and were demanding a new school be built for their students. In a surprise move, county officials approved a new brick structure with a concrete basement. In 1903, forty pupils marched through the hallways on their way to the classrooms of the new Willsburg School House, built near the site of the original school. The old schoolgrounds were used as a community meeting place, and also for church functions. The new school was equipped with two classrooms and two teachers, as the locals fought off an attempt to absorb School District 70 into the Milwaukie School system.

At the Willsburg School House, the student attendance averaged some 30 to 40 pupils per year, compared to the Sellwood School not far away (today’s Sellwood Middle School) which was bulging with over 400 students. By 1911 the Willsburg school bell had rung for the last time, and students in Willsburg were required to transfer to the Sellwood School at S.E. 15th and Umatilla Street.

The closure of the Shindler Furniture Factory not only affected Willsburg residents, but people in Sellwood as well, since the majority of its carpenters and woodworkers resided in Sellwood. The shopowners and bankers of the Sellwood Business Association, then known as the Sellwood Board of Trade, offered $5,000 to anyone willing to establish a Woolen Mill in the area. William P. Old accepted the challenge, and began ordering machinery, while updating the few buildings still serviceable from the Shindler Furniture Factory days. On May 2nd, 1902, hundreds of citizens crowded through the doors of Sellwood’s Firemen’s Hall to celebrate the start of the community’s first Woolen Mill.

The factory was located east of Sellwood, near the present-day intersection of S.E. Umatilla Street and McLoughlin Boulevard. Local businessman Joseph M. Nickum donated a large structure that was once part of the Shidler Furniture Factory for use as a warehouse, and the water rights to Johnson and Crystal Springs Creeks were easily secured by William P. Old to power the newly installed McCormick Turbine waterwheel. Family members of the George Wills Estate offered the use of two acres of land near the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks for the mill.

As part of his plans, William Old promised to have small cottages built close to his factory, so workers wouldn’t have to travel far, or hunt for housing. Restrooms were built specifically for the female mill workers – that was considered an innovative idea in its time. The dangers of spontaneous combustion concerned Mr. Old, and a water tank nearby was connected to a sprinkler system that was installed throughout most of the buildings – although, when tested by fire, that system did not prove to be sufficient… The new Woolen Mill came to a sudden end in February of 1904, when a fire broke out inside the mill by the spontaneous combustion of dry wool and wool dust. Over 200 employees were thrown out of work, and W.P. Olds, instead of rebuilding on the Willsburg property, decided to move his new Portland Woolen Mills northwest to St. Johns on the other side of Portland.

The Ross Scouring Company attempted to revive the Portland Woolen Factory, but closed after operating for only two years – followed by the Multnomah Mohair Mills. The Mohair Mills continued to support the neighborhood with employment for nine years, until hefty tariffs and few orders led to its own demise.

With the Willsburg School House closing and the sale of the Willsburg Train Station already complete, residents were faced with another tough decision. Since there were few business operating in Willsburg to pay taxes to support such services as clean water, sewer services, and road maintenance, those living in area had to look for an alternative. By 1911, the remaining citizens of Willsburg voted to have the town annexed into the City of Portland, as earlier the City of Sellwood had done.

What was left of the Woolen Mills stood empty in Old Willsburg, until Roy T. Bishop came to town. He was looking to invest in a business venture – particularly in manufacturing, in the textile field. U.S. forces were by then busy overseas in Europe, engaged in the First World War, and the government was searching for willing manufacturers to supply the U.S. Army with blankets, uniforms, and other such. Using his experience as manager of the Pendleton Woolen Mills in Pendleton, Oregon, Bishop convinced government officials that he could provide the materials needed to support the U.S. troops.

With the help of the Portland Chamber of Commerce, and a substantial subsidy from the Sellwood merchants, a scouring room, sorting plant, a spinning and carding department, were set up, a variety of looms were ordered, and 60 employees from the neighborhood were hired to fill the allotment request by the government – after which the Oregon Worsted Company was open for business.

Once an armistice was signed between Germany and the Allied nations ending WWI, on November 11th, 1918, all government contracts were cancelled. Roy T. Bishop was free to begin manufacturing worsted yarns and fabrics made exclusively from Oregon sheep. Oregon Worsted went on to be one of Willsburg’s most successful businesses, though by 1919 this area was now considered to be part of Eastmoreland and Sellwood.

However, at the start of the 1920s, those residing in the area east of 27th and Tacoma Street still called themselves part of the community of Willsburg. The Willsburg Dairy was going strong, sending out truck deliveries to Sellwood, Westmoreland, Eastmoreland, north as far as Hawthorne Boulevard, and even to locations the west side of the Willamette River. An announcement in the Western American magazine defined new routes for the Willsburg Dairy, which included Mt. Scott, Woodstock, Albina, Irvington, Alberta, and the Rose City district – quite a large area to cover.

The Dairy was situated at 27th and S.E. Tacoma Street, and continued to deliver dairy products until 1928 when the barn known to many as Willsburg Dairy was sold to make way for expansion of the Eastmoreland Golf Course.

The construction of the McLoughlin Boulevard – the new “Super 99E Highway”, as it was called – was the final nail in the coffin for Willsburg. McLoughlin was completed in 1937, during the Great Depression, by the Works Progress Administration, and what few buildings and structures still remained in Willsburg were swept away to make way for the new highway.

Those curious about where Willsburg citizens once lived should visit the Milwaukie Museum’s website. The curators and volunteers at the Museum have created an historic tour of Milwaukie called “Ardenwald Adventures”. This self-guided tour includes the house once occupied by Jacob Wills and his family; the Hard Shell Baptist Church, once led by George Wills for his congregation; the Shaw House, built near the Willsburg School – and even gives a glimpse of the old Congregational Church built in 1893.

Yes, there once was a town here called Willsburg. It was there even before the brief decade that Sellwood was a separate town, before its own annexation by the City of Portland to become just another neighborhood in this growing city.

Today, Willsburg is just a memory, and it seems that few living here now have ever heard of it. This article gives those folks a chance to learn about this once-important Inner Southeast Portland community…now vanished.