HISTORY: Sellwood in 1888 – grocery shopping in the early days

Published 12:00 am Saturday, December 23, 2023

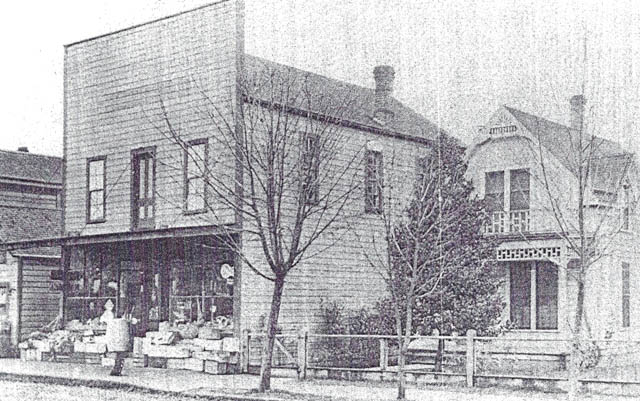

- Knipe's Grocery, between 11th and 13th Avenue on Umatilla Street was nestled in amongst merchant shops – like the Sellwood Bakery, the Umatilla Meat Market, Mrs Crane's Millinery, Maulding Confectionary, Margaret Randall's Boarding House, and the home of THE BEE’s first editor Charles Price. This is a 1908 photo – taken just two years after THE BEE first started publishing.

With Thanksgiving dinner now history, preparing the ultimate holiday meal for Christmas Day can be both time-consuming and stressful.

Trending

Preparations today might include a trip to QFC Market in Westmoreland, New Seasons in Sellwood or Woodstock, or Safeway on Woodstock Boulevard, to find almost any ingredient you need to make that special meal a success.

Customers now have a choice of buying an assortment of turkeys, honey glazed hams, beef tenderloins, or racks of lamb at the meat counter. In the produce section of each store you can find a variety of fresh vegetables, to include green beans for the traditional casserole, fresh potatoes to make scalloped or mashed garlic potatoes, stuffed acorn squash with cranberries and Jell-O salad as a side dish. As for stuffing, that can be purchased in a box off the shelf – or, for those who like to make it as grandmother did, bags of cubed bread can be found in the bakery section, along with assorted spices on the baking aisle. Dinner rolls can be bought by the bag and popped into the oven, ready to serve in no time at all.

And don’t forget dessert! No need to make one from scratch; a pumpkin or apple pie can be bought ready to eat in the bakery section of any of the local stores, though my favorite of each for the price is at Costco. Yes, we really take things like shopping at the grocery stores, and cooking during the holidays, for granted. But it never used to be easy.

If you wanted to fix a special Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner in the 1890s it would take a lot more time, and you’d need visits to more than one grocery store. There wasn’t such a concept as a one-stop shopping center – as Fred Meyer announced about his stores, in the 1960s.

For those living in Sellwood in 1888, according to the City of Portland Directory, you had only two choices for groceries: Edwin Corner’s Country Store and Post Office at about 6th and Umatilla in Sellwood – or Alfred G. Brockwell’s Market at 13th and S.E Nehalem. Both stores probably had no more than two or three aisles of merchandise, both limited in supplies, and neither would have had shopping carts to take around the store. In fact, that these stores were just there at all was an innovation and a major convenience!

The clerk behind the counter of such stores usually ran around the place gathering what items a housewife was asking for, and brought them all to the front counter where they could be wrapped up in brown butcher paper, and tied up with a solid piece of twine for carrying home. Cans of soup and other canned goods were stacked four or five shelves high against the wall, and the proprietor had to use a long wooden pole with metal arms at the end to grasp a can and retrieve it from the top shelf. Shelves stocked with goods and products were often twelve feet high, and this long gripper made a grocer’s life easier. (But customers were probably warned by the clerk to stand clear during this process, to avoid the risk of being whacked on the head by your purchase, if it slipped out of the gripper on the way down.)

Fresh fruit and vegetables weren’t available until summer came, but the apples for an apple pie might have still been available at Miller’s fruit orchard south of Sellwood. In December, most fruit could only be bought, dried, out of a large barrel in the front of the store. (Now you know how fruitcake came to be a Christmas treat!)

Turkey or ham had to be bought at a meat market father down the street, but you still had to pre-order your main dish there as least a month in advance, and then rely on the clerk behind the counter to pick out a good one for you.

While Corner’s and Brockwell’s Grocery Stores were convenient for most residents living within walking distance, a new one was about to open that became more successful than either of them – John Campbell’s Market, on the south side of Umatilla Street, two doors east of 5th. (For those unfamiliar with Portland’s original street system, Campbell’s Grocery would today be the third building west of 11th Avenue on the south side of Umatilla. It’s no longer there, but two separate duplexes built in the 1970s can be found where it was, along this portion of Umatilla.)

Campbell’s was the place to go by the later 1890s. Campbell’s was a small one-and-a-half story building, with large plate glass windows to display all that the store offered to passing customers. The second floor was intended for additional storage for stock items, but John Campbell was very much into local politics, so he offered his upstairs for City Hall meetings and other get-togethers in the neighborhood.

Mr. and Mrs. Campbell probably lived in the back of the store, in fairly small quarters. But then, life revolved around the store, and there was little time to sit at the living room stove and read a book – there wasn’t much thought of any leisure time back then.

Delivery of goods and supplies from Portland’s street markets was still primitive – as reported by THE BEE in the first years of the Twentieth Century: “Campbell used to take a wheelbarrow to the foot of Umatilla Street, pick up groceries from the docked steamer, and later delivered to the homes using the same wheelbarrow.” Not an easy task, considering that the Sellwood Ferry Landing was five blocks away from the store, and the terrain was steep all the way. While the Sellwood Ferry often arrived three times a day, hustling products on a wheelbarrow nine or ten times a day wasn’t easy, even for the most energetic of men. Often, store owners hired a youngster to do the challenging errands and tasks required by a proprietor.

Door-to-door milk deliveries still weren’t available then, because there were only some 150 to 200 homes in the entire town of Sellwood – and most of them were scattered across open country.

Once dairy products or fresh fruits and vegetables did arrive at Sellwood by steamer, ferry, or Interurban rail, they had to be sold quickly, since refrigeration was still lacking in small communities. Bins at the front of the store, packed with ice, could only keep customers’ perishables fresh for so long.

John Campbell had to rely on the help of young lads who arose at dawn and traveled by horse and cart around the neighborhood to take orders for the daily needs of housewives. An efficient grocery boy of that era not only jotted down the order of each and every customer, but had to remember where they lived for the return journey – and he was expected to be a good salesman, too.

When new shipments of fresh greens and milk products arrived at a grocery store, it was up to the delivery boys to contact the customers that they knew were always looking for fresh dairy and agricultural products to tell them about their availability. These energetic delivery boys had to be back to the store by noon, have a quick lunch, and then get back in the wagon and deliver the items ordered before the households started to prepare their evening meal. During the driver’s lunch break, Campbell and his wife probably were busy filling the desired orders and tallying a list that credited the customer’s account. Every day was a busy day for the proprietor and his helpers.

When not making home deliveries, other days were set aside for these young drivers to pick up needed food products from the local farms. Sometimes drivers were required to ride around to five or six outlying farms in one day to collect various products – say, a crate of brown farm eggs in Russellville; a parcel of cabbage in Gresham; maybe fresh berries in Oak Grove. Once these boys were back at the store at the end of the day, there was still no rest – it was time to feed, water, and rub down the horses! It wasn’t uncommon to find that grocery boys often worked between twelve or fourteen hours a day! At this time there were no child labor laws.

Italian farmers and street merchants filled a void that storekeepers couldn’t. Southeast Portland was known for its gardens filled with fresh vegetables, cared for by Italian immigrants. They roamed the streets of Sellwood and other Southeast neighborhoods selling from their laden wagons filled with fresh vegetables. On Fridays, the fish wagon patrolled the streets of Umatilla, Tenino, Tacoma, and 13th Avenue. When unexpected guests stopped in for dinner, desperate housewives couldn’t call back an Italian vendor to fill her needs, so she had to stop her daily chores and hail a delivery boy from Campbell’s when she heard him riding by – or else send one of her children down to the corner grocery store.

Of his many duties as a storekeeper, John Campbell had to create a list of farms in the area, and the products that they could supply to his store. Once train travel became available between the Oregon Coast and Portland, specialty items like Tillamook cottage cheese, Nehalem cheese, and coastal berries could be shipped straight from the farms along the coast to Union Station in downtown Portland, to be held there for pickup. Who picked it up? Of course – the delivery boy!

When telephones began to be installed in the City of Portland, grocery store owners were among the first to get in line to have one installed. Customers who had a phone of their own could now call in orders and have them delivered in a timely manner. Campbell could also order needed supplies to stock his shelves by simply placing an order over the phone instead of sending a boy to pick up whatever product was available on the farm when he rode by.

Dairy products, farm eggs, and hay and grain could be shipped on the Crystal Springs Interurban train and dropped off at the intersection of 13th Avenue and Ochoco Street – locally known as Golf Junction. (It’s at the north edge of the Waverley Golf Club.) A phone call from the vendor would notify the storekeeper when ordered goods would arrive, and it was an easy trip for the delivery boy to travel just a few blocks away to Golf Junction to receive the shipment. Gallons of farm fresh milk and even city mail from downtown Portland often arrived this way to merchants and Sellwood customers starting as early as the first decade of the Twentieth Century.

In addition to his daytime activities of pushing a wheelbarrow to and from the dock, balancing receipts in his accounting book, and stocking his store’s shelves, John Campbell’s second interest was politics. Back in 1887, the independent Town of Sellwood had established a volunteer City Council, and for the following two years John was the elected City Treasurer. Its monthly meetings were held on the second floor of his store!

In 1891, upset with the decisions that this local City Council was making in Sellwood, over 100 people gathered at the front of Campbell’s storefront to show their displeasure and demand that the current volunteer City Council members be replaced. After a heated discussion among the citizens of Sellwood, nine new council members were voted into office to mollify the angry crowd gathered on Umatilla Street. Mischievous boys made the experience even worse, creating effigies of the previous council members and burning them in the street in front of Campbell’s.

When members of the Sellwood Council finally voted for the town to become just a part of the City of Portland in 1893, the final vote tally was taken at Campbell’s Hall over the store.

With the Sellwood City Administrators’ positions abolished, the merchants began to talk about organizing a formal group to deal with additional problems that the Portland City Council might have forgotten about or ignored. Among these were the paving of streets, the availability of clean water, a sanitary sewage system, and improved fire protection in Sellwood.

When the Sellwood Board of Trade was officially established on March 15th, 1901, Mr. Campbell again offered space for their meetings above his store, and Campbell was chosen for the familiar role as the treasurer for the new organization.

It appears that John became so involved in politics that his wife was left to run the store by herself. On numerous occasions when THE BEE was reported on the actions and decisions of the various Sellwood committees that Mr. Campbell was involved with, the editor reminded that the meetings would be held upstairs — above Mrs. Campbell’s store!

As a prominent political figure, among other things, John Campbell was instrumental in establishing a building for the Oregon Historical Society in downtown Portland. Campbell was the owner of one of the largest mineral and rock collections in the Northwest, and he was hoping to add his collection to the Oregon Historical Society’s collections. The Historical Society was then in a small area at Portland’s City Hall, and in 1907 Campbell began pestering city officials to build an auditorium to house the Society’s growing collection of historical documents, and other collections it had received.

So it was that in 1913 the Oregon Historical Society moved to the Tourney Building at S.W. 2nd and Taylor, before eventually settling at its current location at 1200 S.W. Park Avenue.

By 1906, the Campbells had invested heavily in buying property in Sellwood, and were then living comfortably by profitably selling the property. Then it came time to retire, and the Campbells sold their grocery store to Hugh Knipe, who had worked his way up to being its Manager. Actually, John didn’t fully retire, since he was still being appointed to various civic committees involving Sellwood, and pursuing his hobby of collecting rocks and minerals.

Drastic changes were already taking place in Sellwood by the start of the 20th Century: The population had nearly tripled, turning the tiny community into a desirable district where families wanted to settle. Sellwood was in the midst of a housing boom – and with that, more merchants began building on vacant lots and properties along Umatilla Street and 13th Avenue. Competition among grocery stores and markets had become fierce, and proprietors like Hugh Knipe were forced to dream up creative ways to entice customers into their businesses.

When the editor of THE BEE presented the first edition of his newspaper to the public on October 6th, 1906, Knipe’s Grocery Store had one of the first ads on the front page: “Hugh Knipe, Staples and Fancy Groceries, Hardware, Notions, etc. Fresh fruits and vegetables always on hand.”

Advertising was the new way of attracting customers for business owners – especially the grocery stores – and Hugh began advertising in the newspaper with weekly specials. Other markets, like Poole’s Grocery on 17th Avenue, offered Hay and Grain along with Plaster and Cement – while P.E. Hume’s Umatilla Market stated in their newspaper ads that the store offered “The best of meats of all kinds; all are Government inspected.”

Knipe advertised “Saturday specials” for lower prices if paid for in cash only. Store credit was an important selling point for many grocers, as most families lived from paycheck to paycheck. After many years, some customers never got around to paying off their debts, so offering lower prices for cash sales was beneficial to both the shoppers and Hugh Knipe. (Next to the cash register, Hugh had a small wooden box under the counter that contained customer information cards, and a list of what purchases they had bought on credit.)

Hugh managed to keep his store Sellwood’s main grocery market. Staples like sugar and flour were sold by the pound from large barrels, and rice and beans were in wooden drawers behind the counter. “Knipe The Kutter”, as he was known (perhaps for lower prices?), offered customers a variety of soaps, cans of honey, and new cold breakfast cereals called “Post Toasties” and “Post Grape-Nuts” for those people too busy to fix a large morning meal before racing off to work. A large pickle barrel was available for customers to dip into, filled weekly by the pickle man who came by. There was also a large glass jar filled with stick candy on the front counter, for children who had collected a few hard-earned pennies and were ready to spend them.

By then – with residents having some nineteen grocery stores and markets to choose from, in Sellwood and the up-and-coming new community of Westmoreland — Hugh knew he needed to update the old western-style squared-off storefronts that the public still remembered galloping by on horseback back in the 1880’s. In a photo of Knipe’s drawn from the files of the SMILE History Committee, we can see the improvements he made to the store – large, beautiful display windows filled with merchandise, and a set of transom windows running the length of the store. The old porch that graced Campbell’s had been removed and was replaced by a large canopy awning to shade the outdoor goods from the harsh sun during the summer, and the rain in the fall and winter months.

Knipe’s continued to flourish for a few decades more, thanks at least partly to the loyalty of the local residents who continued to prefer places where the proprietor knew everyone’s name – and because Hugh Knipe had supported their household with credit when they faced hard times.

But the rise of the supermarket concept – and self-service store,s like Piggly Wigglys (at Tacoma and 13th), McMarrs, and Safeway (on Milwaukie Avenue), began taking a toll on the traditional neighborhood owner-operated markets – even as the growing quantity and variety of merchants along 13th Avenue, and in Westmoreland along Milwaukie Avenue, was attracting young families to move into the area.

Hugh Knipe began feeling the strain in his personal life, and his marriage ended in a divorce. Then a paralytic stroke sapped his strength around 1929 – after which he and all merchants were hammered by the Great Depression in the 1930s. Sadly, Hugh took his own life with a gun in 1932 while under the care of his sister.

The old Campbell’s Grocery Store that Knipe had operated for so many years was torn down, as were others of the other small shops along the south side of Umatilla Street – and Sellwood began growing into a peaceful residential area. The once-proud main street of Umatilla was relegated to only a few merchants – mainly to shops still located at the busy crossroads at 13th and 17th. The neighborhood’s main streets today are 13th, 17th, and Milwaukie Avenue instead.

How Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner was made, and how these special holidays were celebrated, in the latter half of the Nineteenth Century – and then from decade to decade in the Twentieth Century – is simply just past history today. So it is our pleasure each month to make these memories come alive again for you, helping to add local texture and context to the lives that we enjoy today.