HISTORY: Rev. John Sellwood – real estate and utopian speculator

Published 12:00 am Saturday, December 23, 2023

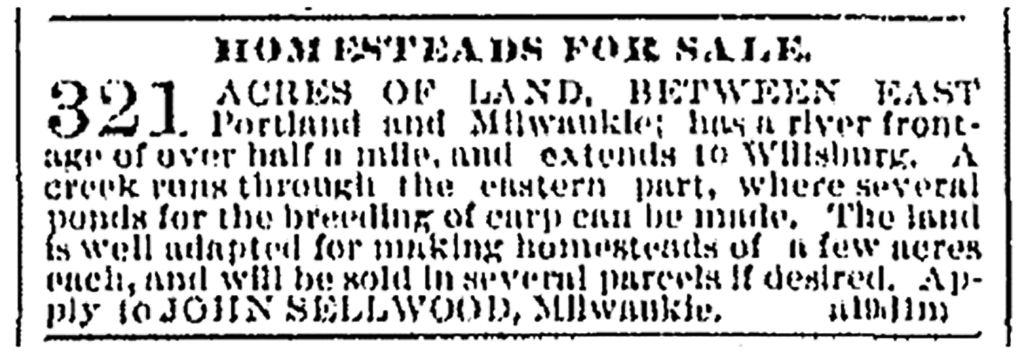

- In this small advertisement in The Oregonian on May 23, 1881, Rev. John Sellwood suggested damming the waters of Crystal Springs Creek and Johnson Creek to create lucrative carp ponds.

In the September issue of THE BEE I described the incident that led to the Rev. John Sellwood’s nearly fatal injuries at the hands of government troops in Panama (then “New Grenada”) in 1856. Other Americans were killed or wounded in the fracas, and the U.S. Government won damages for all, including $10,000 for Rev. Sellwood.

Trending

After months of convalescence, he arrived in the Oregon Territory to serve as an Episcopal priest in Portland, and to minister to inmates at the penitentiary. The final twenty years of his life were spent in service to the congregation of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Milwaukie, whose original 1851 building was moved to Sellwood in 1959 – and has become an icon of the Sellwood neighborhood as the “Oaks Pioneer Church”, just north of the east end of the Sellwood Bridge, on S.E. Spokane Street.

While I was clarifying the details of the “Watermelon Riot” which led to his injuries, other features of John Sellwood’s life began to came to light. He spent most of that $10,000 award on real estate – the largest parcel being the 321 acres that he purchased in 1866 from Henry Eddy, the third owner of land obtained by Henderson Llewellyn in 1848. But Rev. Sellwood also owned properties on the west side of the river, in and around those areas that were expanding to become the City of Portland.

Real estate transfers reported in The Oregonian newspaper between 1865 and 1879 record his purchases and sales of lots, and sometimes entire blocks of property. For example, in 1878 he offered 25-year leases “for homesteads” in a block in Caruther’s Addition, as well as in three blocks in Carter’s Addition. Buyers were asked to contact John Sellwood directly, not an agent – indicating that he was handling the land exchanges by himself, negotiating prices and following through with land titles and deeds.

His biggest investment, those 321 acres on the east side of the Willamette, was a burdensome millstone. As early as 1867 he offered “90 acres of timberland on the road between Milwaukie and Portland”, presumably part of his 1866 purchase. Repeatedly, from 1878 to 1881 he placed advertisements in the Oregonian attempting to unload it in one piece; and when that was unsuccessful, he proposed to sell it as 200 and 100 acre tracts. Those 321 acres later became the foundation of the Town of Sellwood, and later still the Sellwood district of Portland.

His desperation to sell it may have been due to his annual tax payment to Multnomah County on land that was not yet producing any income. As early as 1854, the county collected property taxes to cover the salaries of judges and clerks, a sheriff, a jail, and employees who processed real estate transfers and other necessary services.

While there may have been a few people living at scattered locations on his acreage (a tiny house built in 1876 on Clatsop Street was occupied at least six years before the Sellwood Real Estate Company took ownership), taxes on “built improvements” would have been minimal – but those on 321 acres, multiplied over 16 years, might have been quite substantial.

By 1878 Sellwood was willing to sell parcels of his tract as small as one acre for $25.00. He wrote promotional descriptions, touting its two clear streams (Crystal Springs Creek and Johnson Creek), and its proximity to steamboats that passed on the Willamette River. He claimed (erroneously) that it was “directly across the river from Oswego” the attraction presumably being the Iron Works there that began casting ingots in 1867. In 1879 he pitched it as a new location for the Oregon State Fair (established in 1862), arguing that more people would visit it there than would in Salem.

With no offers, in May of 1881 he made his most farfetched proposition – that “in the Creek through the eastern Part [Johnson Creek] several ponds for the breeding of carp can be made” – without suggesting anyone who might want to purchase the fish.

His desperate prayers were finally answered in June, 1882, when the three investors in the Sellwood Real Estate Company bought the entire piece of land from him for $32,000. Relieved of his financial burden, The Rev. John Sellwood devoted the remaining eleven years of his life to the church in Milwaukie.

However, he did not stay entirely free of real estate. Once his former plat was surveyed and divided into 50 x 100’ lots, he then purchased six blocks of it for $11,520! He died in 1892, and presumably those properties were left in his will to his siblings. Two of his descendants, Harold Sellwood and Mrs. Belle Sellwood, sold real estate in the neighborhood well into the 20th Century – perhaps helping their parents liquidate the family’s inheritance.

It is curious that the Rev. Sellwood apparently never considered using some of his land for another of his schemes: A utopian Christian community. A bachelor, unburdened by the emotional and financial distractions of a wife and children, he was free to develop plans for his imaginary Eden, probably in the 1870s. It was briefly described in “Eden Within Eden”, a book on utopian communities in Oregon, by James J. Kopp, published in 2009 (and available in public libraries).

His utopian community was to be called “Hopeland”, and Rev. Sellwood outlined strict moral parameters for it – including no dancing, no swearing, no arguing, no lying, no gambling, no drunkenness, no trespassing, and no lascivious conduct.

Hopeland never moved further toward reality than the paper on which it was described, which may have been due to Sellwood’s personality and age; although his sketchy paragraphs are not dated, Sellwood would have been 70 years old in 1876. Kopp repeats comments about Rev. Sellwood that were made by fellow pastors at his memorial service. They described him as “enigmatic…strange and eccentric”, although he remained highly regarded for his piety and ministerial service.

There was actually a successful model for such a community not too far away: The religious utopian community of Aurora, founded by William Keil in 1856. Unlike the uncharismatic Sellwood, Keil arrived with several hundred followers from an already-established community in Missouri. Aurora was Christian, but non-denominational, founded simply on the principle of the Golden Rule. Its population swelled to approximately 600 by 1868; the numbers dwindled after Keil’s death in 1877. But the community’s regulations were never as strict as those contemplated by the Rev. Sellwood; dancing may have been allowed, considering the uptempo music performed by the famous Aurora Colony Band. Rules about temperance there are unknown – but the colony had operated a profitable whiskey distillery in Missouri prior to their migration to Oregon.

Perhaps John Sellwood did not share with others his plans for Hopeland, so it remained wishful thinking. People are complex, and it was interesting to discover these other aspects of the Rev. John Sellwood – the busy real estate speculator and utopian dreamer – beyond just the wounds inflicted upon him in an historic incident in what is now Panama, which through the settlement won by the U.S. Government later funded all that he did.